The Yesod team is very pleased to announce the first release of the Warp web server. Warp is a web server for the Wai Application Interface, meaning any Haskell application written against the WAI can use Warp.

Warp was previously part of wai-extra and called SimpleServer. However, after some modifications by Matt Brown it is now ready to be used in a production environment. Since I'm sure everyone wants to see the benchmarks, we'll start with those, and then get to some of the technical details below.

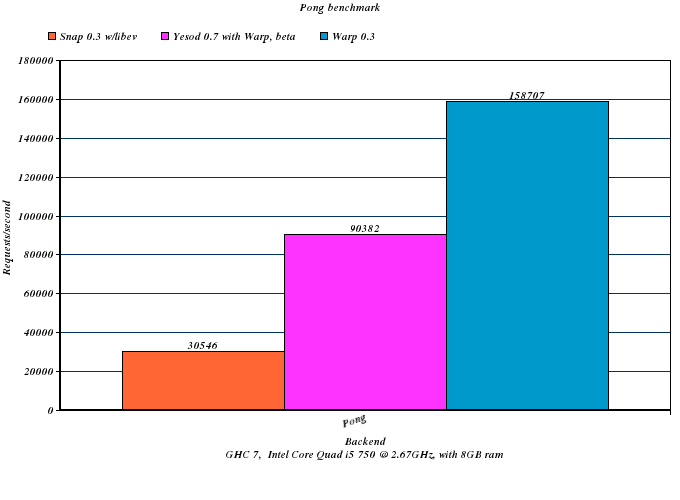

Note: Snap errored out in the above benchmark, and therefore results for it are not available.

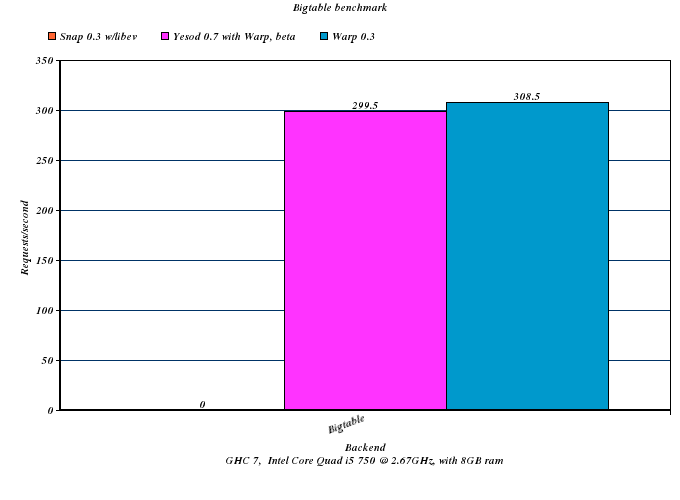

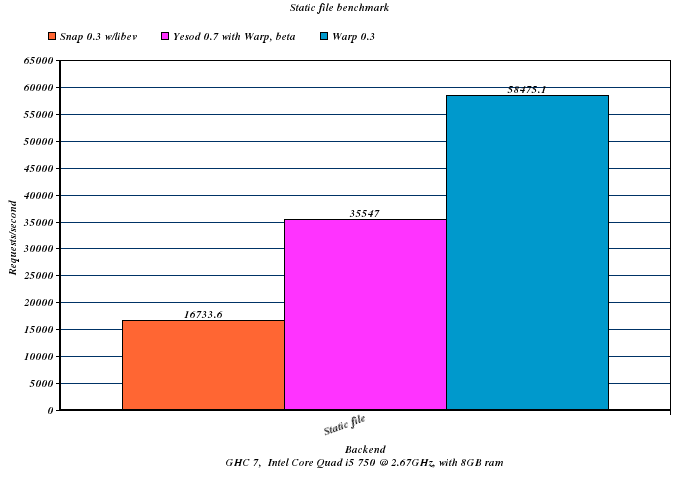

These benchmarks compare the current snap-server 0.3 from Hackage, compiled with the libev backend, against the Warp 0.3 release, as well as a pre-release Yesod 0.7 running on Warp. The difference between Warp and Yesod gives you an idea of the relative cost of Yesod's extra features (such as routing): as you might expect, this difference is relatively large on a small benchmark like PONG, and relatively small on a large benchmark like big-table.

All of the code for these benchmarks is available on github. I asked Gregory and Doug from Snap to look over our results: though they did not get as steep a difference as our results show, Warp still came out ahead: 90k vs 30k. It seems the difference is Doug benchmarked on a 8-core system, while Matt ran our benchmarks on a 4-core system. Snap seems to be better at scaling to >4 cores than Warp, though why this difference exists warrants further investigation.

What I think is even more impressive than the benchmark numbers is the size of the code itself: all of Warp fits in a single 318 SLOC file. However, it is built on the shoulders of giants:

The Warp PONG benchmark increased its response rate three-fold when switching from GHC 6.12 to 7. I would attribute a huge amount of the success here to Johan and Bryan's new event manager, as well as GHC's new inliner.

In order to avoid multiple buffer copies while still minimizing system call overhead, we use blaze-builder extensively. Kudos to Simon and Jasper.

And finally, our entire IO is built on top of John's enumerator package. In fact, I attribute the small code base almost entirely to the usage of enumerator here.

I think that the code base is small enough that we can have an adequate walk-through here. This might also serve as an example of using enumerator and blaze-builder together to produce fast code.

run and serveConnections

The entry point to Warp is the "run" function, which takes a port to listen on and a WAI application to run. A WAI application is just a function that takes a Request and returns a Response. We'll see more details on both of those datatypes later.

run opens up a listening socket and brackets to serveConnection. The bracket just makes sure that the socket is closed even in the presence of exceptions.

serveConnections is also fairly simple: it accepts a single connection, creates a new thread to handle the connection using serveConnection, and loops. While spawning a single thread per connection may be a bad idea with system threads, GHC's light-weight threads fit this pattern very well.

In serveConnection, we see our first bit of mystery. Firstly, for performance reasons, we wrap the whole thing in a catch to ignore any exceptions. We also wrap it inside a finally to ensure that the connection is closed even with exceptions.

However, the interesting code is:

E.run_ $ enumSocket 4096 conn $$ serveConnection'

enumSocket converts a socket into an Enumerator, which reads 4096 bytes of data at a time and feeds the data to an Iteratee. Using the $$ operator simply pipes the data into serveConnection', an Iteratee we'll see in a bit.

The result of this is a new Iteratee. E.run_ actually executes that Iteratee and gives us back an IO action.

serveConnection'

Within serveConnection', we are living in our Iteratee. enumerator is taking care of all the piping and buffering of the input stream for us, so we can just focus on parsing the input data. Note that we still haven't done anything about our output stream back to the client.

Anyway, serveConnection' is just:

serveConnection' = do

(enumeratee, env) <- parseRequest port remoteHost'

res <- E.joinI $ enumeratee $$ app env

keepAlive <- liftIO $ sendResponse env (httpVersion env) conn res

if keepAlive then serveConnection' else return ()

First we parse our request object. This returns us two values: env contains most of the values we'd expect, like path info, query string and remote host. enumeratee is an Enumeratee for piping the request body into the application. Remember that we're living inside an Iteratee monad right now, so there is no way to "extract" the input stream again. Instead, we use this enumeratee to ensure that precisely the right number of bytes are taken from the input stream to fully consume the request body, without going over.

The next line is what actually runs our application: app env (by definition in the WAI) returns back an Iteratee ByteString IO Response. We apply enumeratee (with joinI) to get a new Iteratee that cannot overstep its bounds, and then take out our result. sendResponse sends the response on to the client, and lets us know whether or not we should keep this connection alive. If we are in keep-alive, then we loop; otherwise, we leave this function, letting serveConnection close the connection.

parseRequest

Parsing the request headers involves taking all of the header lines (every line until a blank line) and then parsing those via parseRequest'. takeHeaders (a function I will not explain here) goes ahead and reads in all of the header lines until a blank. A special thanks to Gregory Collins for pointing out a security hole in the initial versions of Warp: takeHeaders now ensures that no header is longer than 1024 bytes, and there are at most 30 headers to avoid a DOS attack.

There's nothing special about parseRequest': it just reads the headers to determine request method, path info, query string, HTTP version, etc.

headers and Builders

A quick detour before we hit sendResponse: the headers function takes an HTTP version, a status, a list of response headers and a bool indicating whether the response is chunked, and returns a Builder.

Builder, as you might guess, is a datatype from blaze-builder. Although Simon or Jasper could do a better job describing it than I, a Builder is essentially an instruction for how to fill up a memory buffer with bytes. So this function generates some buffer-filling instructions.

blaze-builder and blaze-builder-enumerator provide a few different ways of extracting data from a Builder:

toLazyByteString will lazily fill up strict ByteStrings. This works well if we are constructing our Builder purely. However, if our Builder is constructed via a series of IO actions, we would need to perform all of the actions, store all source data in memory, and only then get to produce our output.

toByteStringIO is similar to toLazyByteString in that it works badly with non-pure data. Instead of producing a lazy ByteString, it calls an IO function for each strict ByteString produced. It can be more efficient since it gets to share memory buffers.

builderToByteString is perfect for IO-generated data: it is in fact an enumeratee which takes an input stream of Builders and produces an output stream of strict ByteStrings. Each time a buffer is filled up, it sends out a new ByteString.

sendResponse

sendResponse is where we get to see blaze-builder and its synergy (buzzword!) with enumerator shine. There are three different constructors for a response:

ResponseFile

ResponseFile which has a status code, a list of response headers and a filepath. We provide this in WAI so backends like Warp can provide an optimization by calling sendfile.

We start off by sending the response headers using toLazyByteString and sendMany. This forces all of the data to be pulled into memory and then uses a vectored IO call. In general, this would be a bad move memory-wise; however, since we are only sending headers, which should be small, it's OK.

We next call hasBody. I'll explain its usage here, and then pretend it doesn't exist for the other two constructors. In HTTP, there are two ways (that I'm aware of) for a response to be required to have no body: a response to a HEAD request, and a 204 response. In these cases, we simply send headers and finish.

When we do have a response body, we call sendFile, which uses a system call to send the entire contents of the file in one system call. Next we determine keep-alive. Keep-alive allows us to reuse a connection for multiple requests. It depends on how we send the response body. There are four ways a response body can be sent:

No body at all, as mentioned above. In this case, keep-alive works.

A response body with a content-length. In this case, the client knows precisely how many bytes to read after the response headers before it can expect a new response, so keep-alive works.

A chunked response body. Chunked responses were an added feature of HTTP 1.1. They work well when you don't know the full size of a response before sending it. Instead, you send chunks, each with a header giving its size, followed by a 0-header. This 0-header indicates the end of a response, so the client knows to wait for the next response. Therefore, keep-alive works.

A plain old response body. In this case, the only way for the client to know that it has read the entire response body is for the server to close the connection. In this case, keep-alive does not work.

In the case of file serving, we don't want to use chunking, since we then cannot use the sendfile system call. Therefore, if the application provides a content-length, we can keep-alive; otherwise, we must close the connection.

ResponseBuilder

A ResponseBuilder has a status code, headers and a single Builder. This constructor is not strictly necessary, as all of its funcitonality can be provided by ResponseEnumerator (described next). However, some of our early benchmarks proved that there are performance advantages to ResponseBuilder, so we kept it. In real life, you are much more likely to use a ResponseBuilder than a ResponseEnum, though the latter provides much more power (eg, interleaved IO).

For ResponseBuilder, we use toByteStringIO: it allows us to reuse buffers and not pull the entire reponse into memory. We also use blaze-builders chunking code here when there is no content-length header, assuming the client support HTTP/1.1. Therefore, only HTTP/1.0 clients receiving responses without content-length do not support keep-alive.

ResponseEnumerator

This is the most complicated and most powerful constructor. If you don't entirely understand it, don't worry: I came up with the idea and implemented it, and I still get a little hazy. We're basically taking enumerators- an already complicated concept- and adding more complication.

The motivation goes as such: let's say you want to open a database query and start sending results without caching them in memory. But there's a trick: if there are zero results, you want to return a 404 response. If there is at least one result, you want to send a 200.

In the world of enumerators, we can't "take a break" from being inside the enumerator: once the code starts running, we have to stay there. Therefore, we need some way to notify the web server, from within a database action, what the status code will be. Thus was born ResponseEnumerator:

type ResponseEnumerator a = (Status -> ResponseHeaders -> Iteratee Builder IO a) -> IO a

This says "I'm a function which will take a function that will give back an Iteratee". Wait... what?

Let's try that again: the web server needs to know the HTTP response code and the response headers before it can start sending the response to the client. Once it has the status and headers, it's ready to start receiving data. Remember, in enumerator-land, an Iteratee is a data consumer. So the web server is essentially a function that takes a status and some headers and returns a data consumer: that data consumer then sends chunks of response data out to the client.

So we are handing the web server (as that special function) to the web application and giving it control of how things are run. In our database example, the application code will run its database-query-enumerator and start receiving its stream of results. If it receives zero results, then it can tell the web server that the response is 404; otherwise, it can say 200 and status sending chunks of data, one for each result.

I know it's confusing, but this offers a lot of power to web applications while keeping the full safety and guaranteed resource freeing of enumerators. And for the most part, you can either sidestep the complexity by using ResponseBuilder, or use higher level tools that put an easy-to-use API on the whole thing.

Anyway, let's look at the Warp code for handling this. We define a "go" helper function which takes a status and a list of headers and returns an iteratee (big surprise), and then hand that go function to the ResponseEnumerator. So far so good? Ok, deeper into the rabbit hole.

Within go is what I think is the coolest code in the whole package. We define a chunk' helper function: if the response needs to be chunked (ie, the client is HTTP/1.0 and there is no content-length header), it applies a map over the entire response body to add chunking. If the response is not supposed to be chunked, it makes no changes.

Next, we pipe this monstrosity- together with the headers- through builderToByteString, we produces a stream of ByteStrings. We then send off this stream to iterSocket, which sends the ByteStrings to the client. Finally, we return a keep-alive boolean, using the same rules as ResponseEnum.

Conclusion

Well, that's the whole web server. I think that over all it's still fairly high-level. Some of the lower-level bits (takeHeaders, for instance) can be factored out into some helper libraries so that other packages can also take advantage of these highly optimized iteratees.

I've hoped for a long time that as a community we can start to rally around WAI so the community's different web frameworks can work together to create great middleware, servers, and interfaces. I hope that Warp demonstrates that not only is WAI nice theoretically, it also provides an incredibly efficient interface for creating fast web servers, and therefore fast applications.

If anyone has questions about the Warp code, or how to use WAI from an application side, let me know. I would love to get more frameworks to be able to take advantage of Warp and all the other tools that go along with WAI.